Lee Murray │ New Zealand’s only Shirley Jackson Award winner

A third-generation Chinese Pākehā (European) writer from Aotearoa-New Zealand.

Lee, thank you so much for letting me interview your for “AAPI Hour.” Can you tell me a bit about your background and upbringing, including your cultural heritage?

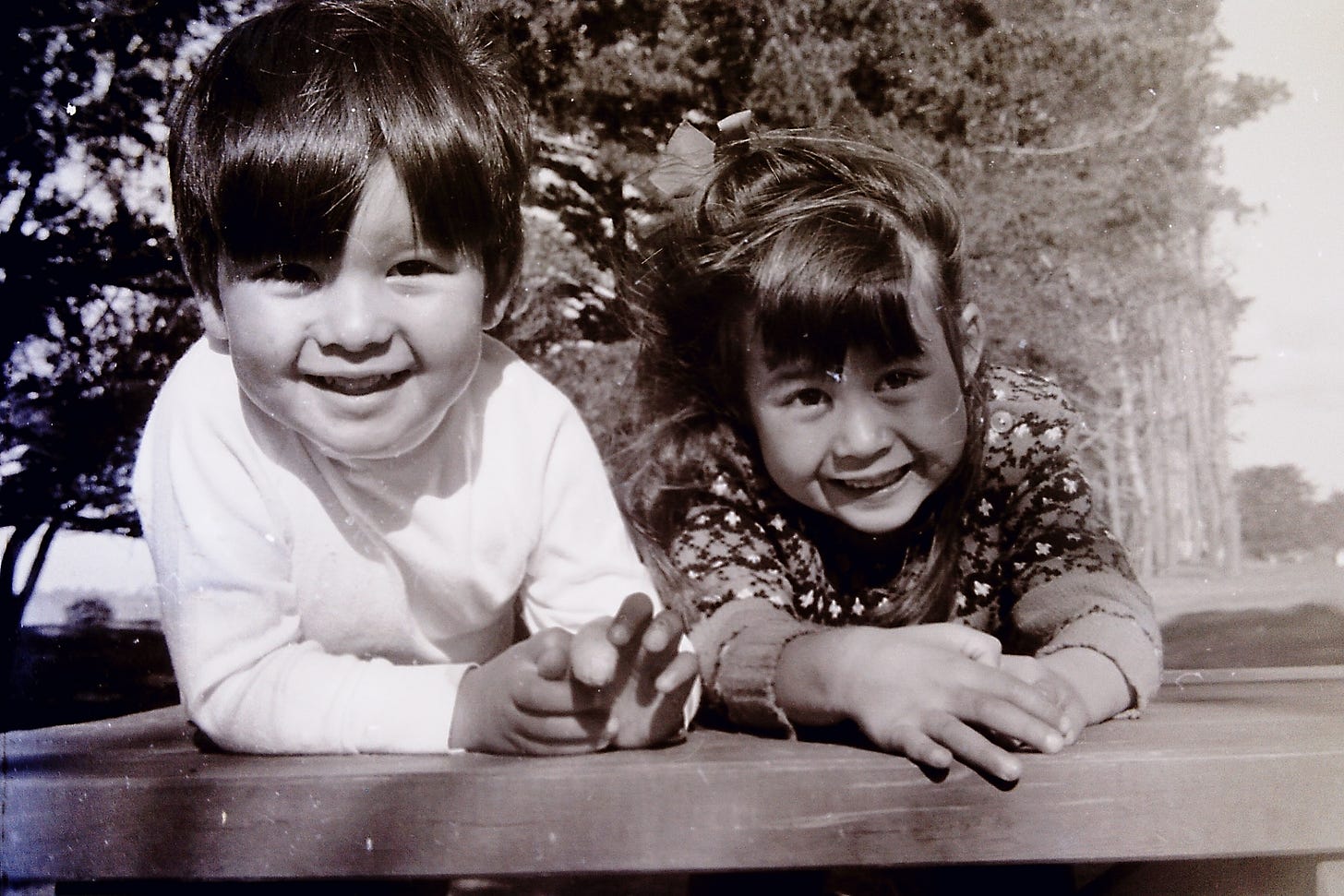

Lee Murray · I’m third-generation Chinese Pākehā (European) writer from Aotearoa-New Zealand. When I was born in the 60s, my dad was working in the bank and the policy in those days was to move accountants around every two years to prevent them getting too established in a particular branch (and possibly committing fraud), so we moved three times in my first six years, living in small towns in New Zealand’s North Island. I got used to be the only Chinese kid at kindergarten, in my class at school, at church, in clubs, everywhere really. There was no one who looked like me in the neighborhoods I lived in—with the exception of my brother, and later my cousins. While growing up, I never saw a book or film that represented my experience as a Chinese New Zealander. John Wyndham’s apocalyptic novel The Chrysalids was the closest I came to ‘relating’ to a text, seeing myself as one of the mutant teens who escaped to New Zealand. As I write in Fox Spirit on a Distant Cloud: “you were one-part willow and one-part mānuka, an out-of-place unbelonging strangeness.”

How do you navigate the balance between preserving your cultural heritage and integrating into the larger society?

Lee Murray · I’d like to say it’s because I am a chameleon who turns green on a leaf or brown when climbing a tree trunk, blending seamlessly and effortlessly into any environment I might find myself in. It should be easy enough, right? After all, I grew up in New Zealand with an Asian mum and a European dad. I’m a product of both cultures, plus the land I was raised on. If only it were that simple. The world isn’t black and white or even green and brown but something far more nuanced.

Can you share some experiences or challenges you’ve faced related to your cultural identity in your personal or professional life?

Lee Murray · You mean apart from the ubiquitous, “where are you from” question?

A few months ago a colleague told me that I represent an “acceptable minority” and I am still struggling with that description. I know it was meant kindly, intended to highlight my relative privilege, to point out that others have a harder road, still it reminds me of the statement made by the New Zealand press when the first Chinese woman arrived on these shores in February 1881, the woman described as “an almond-eyed difficulty”. What I’m hearing is, I should be happy that I’m allowed to be in the room, to take a seat at the end of table, and I am, but I should also remember not to talk too loudly and not to want too much.

Tell me about your professional journey and any career achievements or goals you'd like to highlight.

Lee Murray · I started my life as a research scientist because writing isn’t a ‘real’ job and my dad said I couldn’t make money from writing, and he was kinda right. Making a living from writing is really hard. Making a good living from writing seems unattainable. I’m lucky that my darling supports my creative work, or I’d be a lot thinner. So I guess making a sustainable living is a goal. I’d love to see some of my own work adapted for the screen, or the theatre, or as a graphic novel too, but those are far off dreams rather than concrete goals since I’m not represented by an agent. As far as career achievements go, there have been many wonderful milestones: my first short story sale (“Forecast for April” in Bravado in 2010), my first award (Sir Julius Vogel Award for Best Junior Novel in 2011), co-founding Young New Zealand Writers in 2013 (a decade-long youth development programme), my first literary grant (from the Grimshaw Sargeson Trust in 2020—my 43nd attempt at funding), winning my first Bram Stokers in 2021 (for Black Cranes with Geneve Flynn, and Grotesque), being the only Kiwi to appear in iconic magazine Weird Tales (at least as far as archivists can tell), and gaining life membership of Tauranga Writers and SpecFicNZ for service. There have been other things, too. Just recently, something truly special happened: I was honoured with New Zealand’s Prime Minister’s Award for Literary Achievement in Fiction, appearing alongside some of Aotearoa’s most iconic writers. I’m the first Asian writer to ever be awarded this accolade, which is unbelievably humbling. I’m still reeling from it. You can read about that here. And also here.

Are there any misconceptions or stereotypes about your culture that you’ve encountered, and how do you address them?

Lee Murray · Now that I’m braver, my answer is to turn those misconceptions and misunderstandings, those slights, into a source of inspiration for my writing. Here are two poems about real-life ‘misconceptions’ I’ve encountered. The first is from Bram Stoker Award-winning collection Tortured Willows by Christina Sng, Angela Yuriko Smith, Lee Murray and Geneve Flynn. Yuriko Publishing, 2021. p. 24. The second called, Genuflection, was published in Byline, Tauranga Writers Publishing, 2023, p. 77.

At the Bar

he grins

Asian girls

you know what they say

what do they say?

nice slits

later, I oblige him

with my boning knife

Genuflection

at my new house

with my sister

washing the floors

when you sweep up

the cobbled drive

past the perennial border

bearing pamphlets

glossy with tolerance and love

you poke your head in

and appraise us

two Asian girls

already kneeling

the owner around?

you ask, so clearly

not one of us

What are some aspects of your culture that you wish more people understood or appreciated?

Lee Murray · Deep breath here. Those with Asian heritage, and especially Asian women, often subscribe to the guess-culture form of communication. This communication difference is explained in a now-famous Meta-filler post by Andrea Donderi (byline tangerine). The post is in response to a woman who claimed a friend continually invited herself to stay, and the poster didn’t know how to say no. It reads:

This is a classic case of Ask Culture meets Guess Culture.

In some families, you grow up with the expectation that it’s OK to ask for anything at all, but you gotta realize you might get no for an answer. This is Ask Culture.

In Guess Culture, you avoid putting a request into words unless you’re pretty sure the answer will be yes. Guess Culture depends on a tight net of shared expectations. A key skill is putting out delicate feelers. If you do this with enough subtlety, you won’t even have to make the request directly; you’ll get an offer. Even then, the offer may be genuine or pro forma; it takes yet more skill and delicacy to discern whether you should accept.

All kinds of problems spring up around the edges. If you’re a Guess Culture person—and you obviously are—then unwelcome requests from Ask Culture people seem presumptuous and out of line, and you’re likely to feel angry, uncomfortable, and manipulated.

If you’re an Ask Culture person, Guess Culture behavior can seem incomprehensible, inconsistent, and rife with passive aggression. Obviously, she’s an Ask and you’re a Guess. (I’m a Guess too. Let me tell you, it’s great for, say, reading nuanced and subtle novels; not so great for, say, dating and getting raises.)

Thing is, Guess behaviors only work among a subset of other Guess people—ones who share a fairly specific set of expectations and signalling techniques. The farther you get from your own family and friends and subculture, the more you'll have to embrace Ask behavior. Otherwise you'll spend your life in a cloud of mild outrage at (pace Moomin fans) the Cluelessness of Everyone.

So what does this have to do with me? Well, this guess-culture approach, coupled with the overwhelming Asian expectation that women will sacrifice their own needs and desires to the service of family and community, makes it difficult to navigate a career in an industry that predominantly takes an ask-culture view. Need a review or a blurb, something edited in a hurry so you can submit it to publishers or agents, a mentor to take your work to the next level, help with your charity project? The accepted form in publishing is to reach out and ask your heroes politely. After all, the writer in question can always say no, right? Except Asian women are conditioned not to say no. We must not say no. That’s ridiculous, you’re thinking. Except for me and many other Asian women, it isn’t. It’s that “tight net of shared expectations” that Donderi mentions. I can count on my hand the number of times I have said no, am I am still struggling to reconcile those decisions with my upbringing. Instead, to avoid the angst of saying no, I will say yes. I will say yes and yes, and yes and give and give and give of my time to the detriment of my own work—often without the courtesy of thank you and even more often without payment. I will say yes until I am a walking-talking husk of a person—a feeling which I tried to convey in my poem “tiyanak” in Tortured Willows (p. 28).

tiyanak

innocence

it latches on

as ever

slivering flesh

to gorge on blood and milk

its tiny claws grip-grasping

tiny teeth rasping

feed me, feed me

promise-promise

when it breaks away

it’s only to cry

for more small things; little things

another bead

nothing to you

let it suckle

promise-promise

let it drain you

milking milk-kindness

until you are dried up

a mouthful of bone flour

helpless, you cradle it

barely able

to lift a hand

you stroke its dark hair

shh, you whisper

you’ll be gone soon

Non-Asian readers will be shaking their heads at this. It’s not my problem that you don’t have better boundaries, they’ll say. Put your own oxygen mask on first before helping others, they’ll say. Asian women are taught the opposite. It’s the reason the conscientious Asian girl trope exists. But surely, as a writer I must reach out and ask people for reviews and blurbs for my own work? I certainly do, but possibly less often than ask-culture folks, and the language around my requests is always carefully worded, like dancing on a pinhead, so that the person I am asking can withdraw or refuse without losing face. It’s always a soft ask, rather than the blunter ask-culture version that is the norm in publishing circles.

As a guess culture person, I find the aggressive ‘buy my books’ or ‘share my stuff’ social media of other writers painful (and sometimes offensive). To a guess-culture person, those posts can feel shouty and rude. That’s why you’re more likely to see me share and promote other people’s work than my own. Remember, Asian women aren’t supposed to put ourselves first; we’re supposed to be selfless in the service others. That said, I love the horror community and I love getting those sneak peeks into my colleagues’ work. I want to say yes whenever I can, just not all the time. Not every time.

Here’s another thing: Chinese women are not supposed to accept a compliment. Traditionally, it’s considered rude and immodest. We must deflect or deny or turn the compliment back on the speaker. For ask-culture folks, this can seem like false modesty, or it might come across as if the person is fishing for more compliments. I mean why can’t they just be gracious, say thank you, and move on, right? Only for people from Asian cultures, and particularly women, that is harder than it sounds. Couple that anxiety with the usual writer imposter syndrome and the simple act of having someone congratulate you on a short story acceptance or an award nomination becomes a source of trauma for the Asian writer. Over the years, I’ve gotten better at taking the more Western ask-culture approach of a simple thank you when offered compliments, but it hasn’t been easy to relinquish this aspect of my cultural heritage. Just wait until you get in a room with a bunch of Asian women writers. It’s a running cycle of “you’re the best”, “no, you’re the best”, “no, really, you’re the best”. [I can hear my collaborators Angela Yuriko Smith and Geneve Flynn giggling because we have done this more than once].

So going back to the question—what are some aspects of your culture that you wish more people understood or appreciated—I wish people understood to couch their requests for help and support carefully and to please allow us a little wiggle room to say no when we’re under pressure, and also please don’t take it the wrong way if we find it hard to accept a compliment.

Are there any individuals or role models from your culture who have inspired you, either personally or professionally?

Lee Murray · My grandmother, who came to New Zealand in the 1930s as a refugee with one infant daughter and not a word of English to make her home here. She lost everyone in the war. Not a single family member survived. Elegant and imaginative, her resilience, grace and her work ethic are a source of inspiration to me.

My mother, who risked everything, including the support of her family, when she broke off a proposed arranged marriage with a friend of the family to marry a New Zealand man, a gwailo. Quiet and hardworking, my mother has always led by example, and despite having to leave school at fifteen (no money should be wasted on education for girls), she forged an incredible career, starting off in the bank and working her way up the ladder to become the manager of one of New Zealand’s leading law firms, all while raising four kids. Now, at 80, she teaches tai chi, runs a book club, and is Vice President of her village community.

My daughter, Celine Murray, a queer disabled writer of mixed cultural heritage (including Asian and Māori), whose writing resounds with poetry and truth. Every day she teaches me something new.

Rena Mason, who was the first Asian woman in horror I ever met. At that time she had amassed two Bram Stoker Awards for her writing and was the chair of the StokerCon convention I was attending. I helped her stack some chairs. I know, I know. Not exactly memorable stuff. Poor Rena was so frazzled, she doesn’t even remember the encounter, but I do because it was a turning point for me. A lightbulb moment. Here was an Asian-American woman, at the hub of the horror community, who was writing horror and succeeding. It told me that there was a place for us in horror. Of course, since then she has become a crane sister and a dear friend.

Michelle Yeoh, the first Asian woman to win an Oscar for her performance in the genre feature Everything, Everywhere, All at Once. At the 2023 awards ceremony, she said: “For all the little boys and girls who look like me watching tonight, this is a beacon of hope and possibilities. This is proof that dreams—dream big, and dreams do come true.” Not everyone will succeed of course, but through decades of hard work and resilience, I feel Yeoh has given us the blueprint.

What advice would you give to someone interested in learning more about your culture or building cultural understanding?

Lee Murray · Would it be tacky to say, for deeper insights people could start by reading our work? Books like Black Cranes (collected short stories), Tortured Willows (a collaborative poetry collection), and Unquiet Spirits (essays by Asian women in horror). And should they find a writer whose work speaks to them (I know they will), perhaps explore some more. Check out that writer’s back catalogue or their latest releases. Find out what they’re reading. I would love it if you would consider picking up a copy of my own collection, Fox Spirit on a Distant Cloud, from The Cuba Press. (Yes, I am cringing at the shouty-ness of this).

Here is the back cover blurb:

Wellington, 1923, and a sixty-year-old woman hangs herself in a scullery; ten years later another woman ‘falls’ from the second floor of a Taranaki tobacconist; soon afterwards a young mother in Taumarunui slices the throat of her newborn with a cleaver. All are women of the Chinese diaspora, who came to Aotearoa for a new life and suffered isolation and prejudice in silence. Chinese Pākehā writer Lee Murray has taken the nine-tailed fox spirit húli jīng as her narrator to inhabit the skulls of these women and others like them and tell their stories. Fox Spirit on a Distant Cloud is an audacious blend of biography, mythology, horror and poetry that transcends genre to illuminate lives in the shadowlands of our history.

Thanks so much for having me!

Lee Murray is a writer, editor, poet, and screenwriter from Aotearoa. A USA Today Bestselling author, her titles include the Taine McKenna Adventures, supernatural crime-noir series The Path of Ra (with Dan Rabarts), fiction collection Grotesque: Monster Stories, and several books for children. Her many anthologies include Hellhole, Black Cranes (with Geneve Flynn), and Unquiet Spirits (with Angela Yuriko Smith), and her short fiction appears in Weird Tales, Space & Time, and Grimdark Magazine. A multiple Bram Stoker®-, Australian Shadows-, and Sir Julius Vogel Award-winner, Lee is New Zealand’s only Shirley Jackson Award winner. Winner of New Zealand’s Prime Minister’s Award for Literary Achievement, she is also an NZSA Honorary Literary Fellow, a Grimshaw Sargeson Fellow, and the 2023 NZSA Laura Solomon Cuba Press Prize winner. Read more at leemurray.info