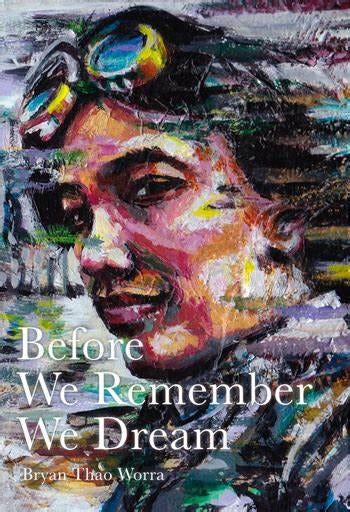

Meet Bryan Thao Worra, who presents internationally on science fiction poetry and the Southeast Asian diaspora. He has presented at the Singapore Writers Festival, the Smithsonian Asian American Literature Festival, the Library of Congress, the League of Minnesota Poets, Poets House, Kearny Street Workshop, the 2012 London Summer Games, and more. His newest collection is American Laodyssey (2024) from Sahtu Press as his community marks 50 years since the end of CIA Secret War in Laos.

Bryan has graciously allowed me to pester him with questions and has responded with eloquence. My questions are in bold. Scroll to the bottom to enjoy his "Zombuddha" reading in Evans City, Pennsylvania, 2021 and a reading of "The Last War Poem" for Valley PBS.

You can follow Bryan Thao Worra online at:

Youtube: Bryan Thao Worra - YouTube

Instagram: Bryan Thao Worra (@bthaoworra)

Tumblr: Vault 555 on Tumblr

Wordpress: thaoworra.wordpress.comAnd coming soon: American Laodyssey — Sahtu Press

Can you tell me a bit about your background and upbringing, including your cultural heritage?

Bryan Thao Worra · That would turn into a very long-story about a Lao infant adopted in the middle of the US Secret War in Laos by a pilot and his family who raised him all over the country including Montana, Alaska, Michigan and the Midwest with way too many science fiction and horror movies, ghost stories and searches for spicy food interspersed throughout. Eventually I became a peculiar literary unicorn, a college dropout who managed to become a full-time poet who made it all of the way to the Olympics.

How has your cultural background influenced your identity and values?

Bryan Thao Worra · This question of course is a bit complicated for me, and it’s difficult to explain to others, so I’ll go with a remark on a Star Trek character I identify with: Worf. His experience resonates with me a lot, because of the way he was introduced to us in the series. It was a radical idea that a Klingon might be a part of the Federation, much like having a Russian and Chinese officer on the bridge. But adopted by humans, when we run into him he’s a bit overbearing as he tries to explain Klingon culture and its virtues at every opportunity. At one point, however, he also runs into other Klingons who help him understand the difference between the ideals of the culture and its lived realities. He’s not alone in wanting the best version of that culture, but he has to be careful not to get used by people who only pay lip service to those values and traditions. And I’ll let readers make their own inferences from there.

What are some of the most important cultural traditions or practices in your family or community?

Bryan Thao Worra · You’ll often hear our community talk about the traditional Lao New Year, such as the Year of the Nak (or Dragon/Naga) that will take place this April, and the importance of the tahk baht almsgiving ceremonies. Tourists have often thought it’s shameful that Buddhist monks have to beg for food, but in fact, in our culture it’s an opportunity for us to regularly practice compassion and build that into our daily practice. There is a belief in non-attachment and resilience in many of our sayings and customs, in order to find patience and resolve, and to recognize the impermanence of things in the world. Not to say it is without meaning, but to appreciate what REALLY matters and who we most feel connected to in the various situations of our lives. If you’re lucky, you might also get to be part of a baci ceremony that is a symbolic ritual to remind us our interconnection to one another even as the various forces of life and circumstance might keep us apart for days and even years and lifetimes.

How do you navigate the balance between preserving your cultural heritage and integrating into the larger society?

Bryan Thao Worra · I was fortunate to have teachers who encouraged me to have an open mind about where our culture was, and to appreciate that societies are always in a certain dynamic flux. That they change isn’t a liability or a weakness or failing, but a feature to embrace with curiosity. Back in the day, as I made may way back to Lao society, I think we were all more curious what parts of who I am and how I wanted to interact with others persisted even though I’d been away for over two decades. Knowing that our roots went back over 700 years made it easy to respect that maybe there was something we were trying to hold on to, something worth trying to become, compared to America, which was barely over 200 years old. And as it was, seeing the dysfunction, the unhappiness and conflict, I could appreciate the best of what the US was trying to reach for, but I certainly wasn’t going to say the US was always in the right any more than any other person. But in the US, we also had freedoms of speech and an openness to different opinions and perspectives that other parts of the world might find more challenging as we try to preserve and discuss our heritage. I think there’s something to be said for being in a sandbox where what you say could change nothing, or it could change everything. But that’s a whole long lecture.

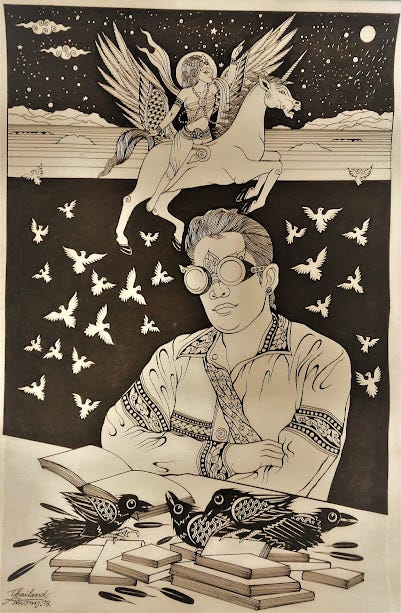

Collaborating this season with the artist Bay Koulabdara on American Laodyssey (Sahtu Press, 2024) has been an important reminder on how we decolonize ourselves and get out of a mindset that we have to do things the way others do it in order to get taken “seriously”. Much like I learned with Vongduane Manivong on DEMONSTRA and Nor Sanavongsay and Sisavanh Phouthavong Houghton on Before We Remember We Dream, the community still doesn’t have a vast range of books to turn to for examples of what Lao and Lao American poetry can be. And I feel privileged that we can explore this and push the boundaries of graphopoetics, the inclusion of visual art, photography, and other things that genuinely interest us. This seems preferable to trying to go broke putting out a book of poetry that looks like a book of poetry from some mainstream “serious” poet going broke.

Tell me about your professional journey and any career achievements or goals you'd like to highlight. Can you share some experiences or challenges you've faced related to your cultural identity in your personal or professional life?

Bryan Thao Worra · Arguably you could say that I’ve been at this a little over 30 years now if we’re discussing poetry and writing that I’m creating that I wasn’t assigned to write for a class, and that I took risks to just get those pieces out there in the world. Over the course of my journey, I earned the distinction of being the first Lao American to receive an NEA Fellowship in Literature in 2009 for poetry. This was often despite discouragement from other emerging writers and even some established writers. One of the hardest parts was learning when you don’t have to listen to other people even as much is made of literary and artistic community in BIPOC spaces.

But in my persisting, I went on to receive over 20 literary, academic and professional awards, including an Asian Pacific American Leadership Award in 2009 and the title of Lao Minnesotan Poet Laureate. As mentioned earlier, in 2012, I was selected as the Lao delegate to serve as a Cultural Olympian during the London Summer Games. I was the very first Lao American to serve as the president of the international Science Fiction Poetry Association, and spent 6 years advocating for speculative poetry with a network of 400+ poets in 19 countries. As the author of 9+ books, I’ve seen my work translated in Spanish, French, German, Chinese, Japanese, Korean, Thai, Tagalog, Bengali, and Lao. I’ve presented at the Singapore Writers Festival, the Smithsonian, Poets House, the Library of Congress, and institutions across the globe. I’m cited in the Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics and the Historical Dictionary of Asian American Literature and Theater and over 27 academic papers.

I mention all of this because it’s also part of a conversation on metrics. For all of these distinctions, at the same time you’ll also run into plenty of institutions and communities where I’m considered invisible. In our first 50 years in the US, as part of a community of nearly 250,000 Lao refugees, there have been fewer than 50 books in our own words, on our own terms. I wrote many of them. But, as far as the Academy of American Poets is concerned, even though I’ve been in the US since 1973, my work isn’t something to include in conversations. You’ll find similar reactions in Minnesota literary organizations and Asian American poetry networks or groups like the Science Fiction Writers of America. But you know what? Still we create. And we learn what it really means to write and get ourselves out there.

Are there any misconceptions or stereotypes about your culture that you've encountered, and how do you address them? What are some aspects of your culture that you wish more people understood or appreciated?

Bryan Thao Worra · In many ways, the near invisibility of the Lao as a culture on the radar of most people might well be an advantage in that few people had stereotypes or preconceived prejudices they could apply to us. Often, if I faced discrimination and bigotry, it was for being non-white, and in some cities, I was called the slurs for whatever brown person the locals hated most at the time. In some states it was an “Eskimo,” others a “Jap,” “Chink,” “’Spic” or whatever. You learn to be philosophical about that.

In the 20th century, US paramilitary advisors and others often described the unwillingness of Lao to kill other people as a character flaw while trying to find more suitable recruits for their interests in Southeast Asia and what has come to be known as the Vietnam War, or the American War, depending on your perspective. Our heritage reaches back to well over 700 years, and made an effort to live in harmony with over 150 ethnic groups and cultures within our historical territories. In a space approximately the size of Utah or Minnesota, that’s no easy task, even as traditional beliefs mixed with Hinduism, Buddhism, Taoism, whatever worked within the moment. Laos once considered itself the realm of a million elephants, but we should bear in mind that those were terrifying war elephants, not gentle cousins of Dumbo, and today’s choice for many Lao to seek a modest and peaceful path IS a choice. The Lao journey, including its years as a nation seeking to remain neutral within conflicts should rarely be read as one of weakness or impassiveness, indifference, or ignorance, but an effort at modeling hospitality and finding the courage to be the responsible ones in conflicts. This has, of course been an imperfect process. And yet, for all of that turbulence in our history, given the opportunity to “not be Lao” as various forces come through over the centuries, every day, millions yet still choose to be Lao and to try again. And I think there’s a poetry in that worth exploring.

Are there any individuals or role models from your culture who have inspired you, either personally or professionally?

Bryan Thao Worra · That’s a bit of a challenge because in Laos, historically, the names of poets were almost always kept anonymous, even as we were valued as the eyes of the city. The traditions reserved names for the wealthy and the elite, and even then, in many instances the truth of their lives in those ages may not fully correspond to the written records. But I do think of the example of Phia Sing (1898-1967), who was a royal chef and master of ceremonies to the kings of Laos, and he was also believed to be a physician, architect, choreographer, sculptor, painter and poet. And while we don’t have many direct examples of his work today, I feel a certain assurance that those who before me took on so many diverse roles in the course of their lives.

What advice would you give to someone interested in learning more about your culture or building cultural understanding?

Bryan Thao Worra · Way back in the day, an old volunteer from the US used to opine that anyone who’s talking English doesn’t know the first thing about the real problems that are going on in Laos, which was wildly reductive but helpful to keep in mind, I’ve found. But getting to understand more about the Lao diaspora and the real worldviews Lao hold is a process that will take years. Many have found you can’t just parachute in with a guide book and some recipes and expect to immediately understand the traditions we’re trying to preserve and the changes we’re reaching for, and what’s actually changing us. Things move slowly and quickly, and your best approach is going to come from being committed to stick around for a while, possibly even a lifetime or two.

Do you have any favorite books, movies, or art forms that you feel represent your culture well and that you'd recommend to others?

Bryan Thao Worra · At the moment, this is all still a very big moving target for everyone. It wasn’t until a little over ten years ago that we saw our first Lao horror film, Chanthaly, by director Mattie Do. Most of our best speculative work is going to be found in cinema and short films these days, like Bai Non (“Go To Sleep”) by Phet Mahathongdy O’Donnell which takes on the traditional spirit known as the Phi Am that inspired a certain 1980s horror movie director back in the day. Some might also enjoy the films Nerakhoon: The Betrayal, and Origin Story: A Documentary. I would certainly encourage poets to look at the work of Krysada Panusith Phounsiri, Do Nguyen Mai, and Sokunthary Svay, Bunkong Tuong, Barbara Jane Reyes, Renee Ya, and Hai Dang Phang, among others.

Is there anything else you would like to share about yourself or your culture that we haven't covered?

Bryan Thao Worra · I’ve gone on at length here, but I think I’ll just close it with a key thought for emerging writers: A poet’s least important task is demonstrating the art we can create and share with the world when conditions are perfect. Be patient with yourself, and good luck.

And